We hope you enjoy this preview chapter from Pyr Books!

A whisper of evening breeze off the lake brushed Mihn’s face as he bent over the small boat. He hesitated and looked up over the water. The sun was about to set, its orange rays pushing through the tall pine trees on the far eastern shore. His sharp eyes caught movement at the tree line: the gentry moving cautiously into the open. They were normally to be found at twilight, watching the sun sink below the horizon from atop great boulders, but today at least two family packs had come to the lake instead.

“They smell change in the air,” the witch of Llehden commented from beside him. “What we attempt has never been tried before.” Mihn had noticed that here in Llehden no one called her Ehla, the name she had permitted Lord Isak to use; that she was the witch was good enough for the locals. It was for Mihn too, however much it had confused the Farlan. Mihn shrugged. “We are yet to manage it,” he pointed out, “but if they sense change, perhaps that is a good sign.” His words provoked a small sound of disapproval from Xeliath, the third person in their group. She stood awkwardly, leaning on the witch for support. Though a white-eye, the stroke that had damaged her left side meant the brown-skinned girl was weaker than normal humans in some ways, and glimpses of the Dark Place hovered at the edges of her sight, a shred of her soul in the place of dark torment because of her link to Isak. Her balance and coordination were fur-ther diminished by exhaustion: Xeliath was unable to sleep without enduring dreams terrible enough to destroy the sanity of a weaker mind. Mihn had been spared that at least; the link between them was weaker, and he lacked a mage’s sensitivity. Together they helped Xeliath into the boat. The witch got in beside her and Mihn pushed it out onto the water, leaping aboard once it was clear of the shore. He sat facing the two women, who were both wrapped in thick woollen cloaks against the night chill. Mihn, in contrast, wore only a thin leather tunic and trousers, and the bottom of each leg was bound tight with twine, leaving no lose material to snag or tear.

Mihn caught sight of an elderly woman perched on a stool at the lake-side and felt a flicker of annoyance. The woman, another witch, had arrived a few days earlier. She was decades older than Ehla, but she was careful to call herself a witch of Llehden—as though her presence in the shire was on Ehla’s sufferance alone. She had told Mihn to call her Daima—knowledge—should there be a need to differentiate between them. For almost fifty years Daima had laid out the dead and sat with them until dawn, facing down the host of spirits that are attracted by death in all its forms. She had a special affinity for that side of the Land, and had ushered ghosts and other lost souls even to the Halls of Death, going as far within as any living mortal Ehla knew of.

The old woman had reiterated again and again the dangers of what they were about to attempt, particularly marking the solemnity and respect Mihn would need to display. That she was presently puffing away on a pipe as she fished from the lakeshore did not exactly impart the level of gravity she had warned them was imperative to their success.

With swift strokes he rowed to the approximate centre of the lake and dropped a rusty plough blade over the edge to serve as anchor. Once the oars were stowed the failed Harlequin took a moment to inspect the tattoos on his palms and the soles of his feet, but they remained undamaged, the circles of incantation unbroken.

“Ready?” the witch asked.

“As ready as I ever will be.”

“The coins?”

He could feel the weight of the two silver coins strung on a cord around his neck. Mihn’s extensive knowledge of folklore was serving him in good stead as he prepared for this venture. It was common practice for dying sinners to request a silver coin between their lips, to catch a part of their soul. Whoever sat with them until dawn would afterwards drop the coin in a river, so the cool water could ease any torments that might await them. Daima had provided this service often enough to know where to find two such coins easily enough.

“They are secure,” he assured them.

“Then it is time,” Xeliath rasped, pushing herself forward so that Mihn was within reach. The young woman squinted at him with her good right eye, her head wavering a moment until she managed to focus. She placed her right hand on his chest. “Let my mark guide you,” she said, stiffly raising her left hand too. That, as always, was half closed in a fist around the Crystal Skull given to her by the patron Goddess of her tribe. “Let my strength be yours to call upon.”

Ehla echoed her gesture before tying a length of rope around his waist. “Let my light keep back the shadows of the Dark Place.”

Mihn took two deep breaths, trying to control the fear beginning to churn inside him. “And now—”

Without warning Xeliath lurched forward and punched Mihn in the face. A sudden flash of white light burst around them as the magic humming through her body added power to the blow. The small man toppled over the edge of the boat, dropping down into the still depths. Ehla grabbed at the coil of rope fast disappearing after Mihn.

“I’ve been looking forward to that bit,” Xeliath said, wincing at the effect the punch had had on her twisted body.

The witch didn’t reply. She peered over the edge of the boat for a moment, then looked back towards the shore. The sun was a smear of orange on the horizon but it wasn’t the advancing evening that made her shiver unexpectedly. In the distance she saw Daima set her fishing rod down while barely a dozen yards from the old woman, a pair of gentry crept forward to drink from the lake.

Ehla pulled the hood of her cloak over her head and did the same for Xeliath before helping the girl to sit down in the curved hull of the boat. Above, the sky slowly darkened while they made themselves as comfortable as they could.

“Now it is up to Mihn,” she said quietly.

* * *

Legana felt the touch of Alterr’s light on her face and drew back a fraction until her face was again shadowed from the moon. With her half-divine senses open to the Land she could feel her surroundings in a way that almost made up for her damaged eyesight. The woman she was stalking was no more than two hundred yards off and coming closer. Like a snake tasting the air Legana breathed in the faint scents carried on the breeze. The spread of trees and the slight camber of ground unfolded in her mind: a complex map of taste, touch, and other senses she had no names for. Within it the other woman shone, illuminated by a faint spark within her that tugged at Legana’s weary heart.

She replaced the blindfold and waited for the right moment to step out from the shadows. The blindfold hampered little, and it made her appear less of a threat; it did Legana no harm to remain cautious and look feeble. Her voice had been ruined by the mercenary Aracnan’s assault and normally she would be forced to communicate by means of the piece of slate that hung from a cord around her neck—but the woman had the spark within her, as Legana herself did. It was faint—she had clearly strayed far from the Lady— but Legana hoped it would be enough for her divine side to exploit.

When the woman was only a dozen yards away Legana moved out from behind a tree. The woman gave a yelp of surprise and drew an axe and a short-sword in one smooth movement. In response Legana leaned a little more heavily on her staff and pushed back the hood of her cloak so the woman could see the blindfold clearly.

“Not a good night to be walking alone,” Legana said directly into the woman’s mind.

The other glanced behind her, wary of an ambush. As she did so the scarf over her head slipped, showing her head was nearly bald. “How did you do that? Who says I’m on my own?”

“I know you are.”

“You’re a mage without any fucking eyes, what do you know?” the stranger snapped. She was shorter than Legana by some way, and more pow-erfully built. The lack of hair made her look strange and foreign, but as soon as she spoke her accent labelled her as native Farlan.

“I know more than you might realise,” Legana replied, taking no offence. A small smile appeared on her face: before Aracnan’s attack she had been just as prickly as this woman. It had taken an incurable injury to teach her the value of calm. The quick temper of her youth would do a blind woman no good, whether or not she was stronger than before.

“For example,” Legana continued, “I know you strayed from your path a long time ago—and I know I can help you find it again.”

“Really? That’s what you know, is it?” The woman shook her head, con-fused by the fact that someone was talking thought to thought, but anger was her default state, as it had once been for Legana, and it presently over-rode her questions. “Looks to me like you’re the one who’s lost the path, and being blind I’d say you’re in a lot more trouble than I am out here.”

“What is your name?”

For a moment she was silent, staring at Legana as though trying to work out what threat she might pose. “Why do you want to know?” she asked eventually.

Legana smiled. “We’re sisters, surely you can tell that? Why would I not want to know the name of a sister?”

“The Lady’s fucking dead,” the woman spat with sudden anger, “and the sisterhood died with her. If you were really one of us you’d have felt it too, mad, blind hermit or not.”

Legana’s head dipped for a moment. What the woman said was true. Legana had been there when the Lady, the Goddess Fate, had been killed. The pain, both of that loss and of her own injuries that day, was still fresh in Legana’s mind.

“She’s dead,” she said quietly, “but sisters we remain, and we need each other more than ever. My name is Legana.”

“Legana?” the woman said sharply. “I know that name—from the temple in Tirah. But I don’t recognise you.”

“I’ve changed a little,” Legana agreed. “I couldn’t speak into another sister’s mind before.”

“You were the scholar?” the woman asked sceptically. “The one they thought would become High Priestess?”

Legana gave a sudden cough of laughter. “If that’s what you remember we were at different temples! I was the one she beat for insolence every day for a year—I was the one who excelled only at killing. I was sold off to Chief Steward Lesarl as soon as I was of age.”

The woman let her shoulders relax. Grudgingly she returned her weapons to her belt. “Okay, then. You were a few years younger, but we all heard about the trouble you caused. I’m Ardela. What happened to your voice?”

Legana’s hand involuntarily went to her throat. Her skin was paler even than most Farlan—as white as bone, except for Aracnan’s shadowy handprint around her neck. Underneath were some barely perceptible bumps: an emerald necklace had sealed her bargain with Fate when Legana had agreed to be her Mortal-Aspect, but the violence done subsequently had somehow pushed the jewels deep into her flesh.

“That I will tell you when I tell you my story,” Legana said. “First, I want to ask you, where are you going by yourself in a hostile land? You don’t strike me as the sort to be left behind by the army.”

Ardela scowled. “The army wouldn’t have noticed if half the Palace Guard had deserted; they’re in chaos after Lord Isak’s death.”

“So why are you here?”

“I think my time with the Farlan is done,” Ardela said after a long pause.

“Doubt it would be too safe for me to return to Tirah; a few grudges might come back to haunt me.”

“Then where are you going?”

“Where in the Dark Place are you going?” she snapped back. “What’s your story? You’re a sister, but a mage too? You’re crippled, but wandering out in the wilds all by yourself? There are Menin patrols out this far, and Farlan Penitents who’ve deserted, and Fate knows what else lurking—”

Legana held up a hand to stop Ardela “I’ll tell you everything; I just want to know whether you are looking for renewed purpose, or just a job in some city far away from your ‘grudges.’ I want to know whether you still care for the daughters of Fate.”

Ardela didn’t answer immediately; for a moment her gaze lowered, as though she were ashamed. “Whatever I care for, I cannot return to Tirah,” she said at last.

“Could you stand to meet a temple-mistress, if it were somewhere other than Tirah?”

“You asking whether they’d accept me, or I’d accept them?”

“Their opinion will be my concern, not yours. We must all start afresh if we’re to survive this new age.”

“Yes, then—but it don’t matter, the Lady’s dead.” A spark of her former fierceness returned to Ardela’s voice. “Whatever you think you can do, the Daughters of Fate are broken.”

“But perhaps I can remake them,” Legana said. “I don’t know how yet, but I’m the only one who can draw them back together. They’re the only real family I’ve ever had and I won’t just stand back and watch them drift away. Without the Lady we’ve lost the anchor in our hearts; we’re bereft. Who knows what our sisters will do if the ache of her loss stops them caring about anything?”

“I do,” Ardela said in a small voice. “I’ve lived that way for years now.”

“Then let’s do something more with ourselves,” Legana suggested, holding a hand out to the woman.

Ardela took it, and allowed herself to be led by a half-blind woman into the darkest part of the wood, where Legana had sited her small camp. On the way Legana told Ardela what had happened to her throat, how she had become the Lady’s Mortal-Aspect and then witnessed her death a few days later.

When Legana mentioned Aracnan, and the one whose orders he must have been following—the shadow, Azaer—Ardela flinched, and her own story began to pour out of her. She cried, ashamed for her employment by Cardinal Certinse, whose entire family had served a daemon-prince, and sor-rowed by the savagery and depravity of her life during those years. In the darkness the women held each other and wept for what they had lost. Long before dawn broke they knew they shared an enemy.

y

He fell through a silent storm, tossed carelessly like a discarded plaything. Tumbling and turning, he dropped too quickly even to scream. Unable to see, unable to speak, he tried to curl into a ball and protect his face from the thrashing storm, but the effort proved too much. There was no energy in his limbs to fight the wild tumult, nor breath in his lungs to give him strength. But as he fell deeper into darkness, the panic began to recede and some measure of clarity started to return to his thoughts.

The storm, he realised eventually, was chaotic, assailing him from all directions, and though every part of his body told him he was falling, as the blind terror began to fade he realised he was in a void, a place where up and down held no meaning. He was apart from the Land, tumbling through chaos itself—until Death reached out to claim him.

All of a sudden the air changed. Mihn felt himself arrive somewhere with a jolt that wrenched him right around. His toes brushed a surface beneath him and gravity suddenly reasserted itself. He collapsed in a heap on a cold stone floor, a sharp pain running through his elbows and knees as they took the impact. Instinctively he rolled sideways, curling up, his hands covering his face.

Once his mind stopped spinning Mihn took a tentative breath and opened his eyes. For a moment his vision swam and he moaned with pain. Then his surroundings came into focus. A high vaulted ceiling loomed some-where in the distance, so vast, so impossibly far that his mind rebelled against the sight. Before Mihn could understand where he was he had rolled over again and was vomiting on the stone floor.

Almost instantly he felt a change within himself as sight of something mundane became a lodestone for his thoughts. Underneath him were flag-stones, as grey as thunderclouds, pitted with age. He struggled to his feet and lurched for a few drunken steps before regaining his balance. Once he had done so he looked at his surroundings—and Mihn found himself falling to his knees again.

He was in the Halls of Death—the Herald’s Hall itself. All the stories he had told, all the accounts he had read: none of them could do justice to the sight before him. The human mind could barely comprehend a place of magic where allegory was alive enough to kill. The hall stretched for miles in all directions, and was so high he felt a wave of dizziness as soon as he looked up. Gigantic pillars stood all around him, miles apart and higher than moun-tains, all made of the same ancient granite as the roof and floor.

There was no one else there, Mihn realised. He was quite alone, and the silence was profound. The vastness of the hall stupefied him. Mihn found himself unable to fully comprehend so unreal a space, made more unworldly by the silence and the stillness in the air. Only when that stillness was broken—by a distant flutter from above—did he find himself able to move again. He turned, trying to follow the sound, only to yelp with shock as he saw a figure behind him where there had been no one before.

He retreated a few steps, but the figure didn’t move. Mihn didn’t need the accounts he’d heard about the last days of Scree to recognise the figure: with skin as black as midnight, robes of scarlet, and a silver standard, it could only be the Herald of Death, the gatekeeper of His throne room and marshal of these halls.

The Herald was far taller than Mihn, bigger even than the tallest of white-eyes. Prominent ears were the only feature of the hairless black head. Eyes, nose, and mouth were indentations only, token shapes to hint at humanity, which served only to make the Herald more terrifying.

Behind the Herald, away in the distance, Mihn saw a great door of white bones. Now, in the shadows of the hall’s vaulted roof, there was faint movement: indistinct dark coils wrapped around the upper reaches of the pillars, then dis-sipated as others flourished, coming into being from where, he could not tell.

Death’s winged attendants. In Death’s halls, other than Gods, only bats, servants of the Chief of the Gods Himself, could linger. Bats were Death’s spies and messengers, as well as guides through the other lands. If a soul’s sins were forgiven, bats would carry the soul from the desolate slopes of Ghain, sparing it the torments of Ghenna.

The Herald of Death broke Mihn’s train of thoughts abruptly by ham-mering the butt of the standard on the flagstone floor. The blow shook the entire hall, throwing Mihn to the ground. Somewhere in the dim distance a boiling mass stirred: vast flocks of bats swirled around the pillars before settling again.

When Mihn recovered his senses the Herald was staring down at him, impassive, but he wasn’t fooled into thinking he would be allowed to tarry.

He struggled to his feet and took a few hesitant steps towards the huge gates in the distance. The rasp of his feet across the floor was strangely loud, the sound seeming to spread out across the miles, until Mihn had recovered his balance and could walk properly. Obligingly the Herald fell in beside him, matching his uneven pace. It walked tall and proud at his side, but otherwise paid him no regard whatsoever.

After a moment Mihn, recovering his wits, realised some subtle compul-sion was drawing him towards the ivory doors of Death’s throne room. The doors themselves were, like the rest of the hall, of a vastness beyond human comprehension or need.

As he walked he became aware of a sound, at the edge of hearing, and so quiet it was almost drowned out by the pad of his footsteps and the clink of the Herald’s standard on the flagstones. In the moments between he strained to hear it, and as he did so he detected some slow rhythm drifting through his body. It made him think of distant voices raised in song, but nothing human; like a wordless reverence that rang out from the very stone of the hall.

It intensified the awe in his heart and he felt his knees wobble, weak-ening as the weight of Death’s majesty resonated out from all around. His fin-gers went to the scar on his chest. It had healed soon after he and the witch left Tirah, but the tissue remained tender, an angry red.

He kept his eyes on his feet for a while, focused on the regular movement and the task at hand, until the moment had passed and he felt able to once more look up towards the ivory doors. They appeared no closer yet, several miles still to walk, by Mihn’s judgment.

He suddenly remembered an ancient play: the ghost of a king is granted a boon by Death, to speak to his son before passing on to the land of no time.

“‘The journey is long, my heir,’” Mihn whispered to himself, “‘the gates sometimes within reach and at others hidden in the mists of afar. They open for you when they are ready to—until then hold your head high and remember: you are a man who walks with Gods.’”

After a few more minutes of silence he began to sing softly; a song of praise he had been taught as a child. The familiar, ancient melody immedi-ately reminded him of his home in the cold north of the Land, of the caves the clans built their homes around and the cavern where they worshipped.

When he reached the end of the song he moved straight on to another, preferring that to the unnatural hush. This one was a long and mournful deathbed lament, where pleas of atonement were interspersed with praise of Death’s wisdom. Considering where he was going it seemed only sensible.

Copyright © 2010 by Tom Lloyd

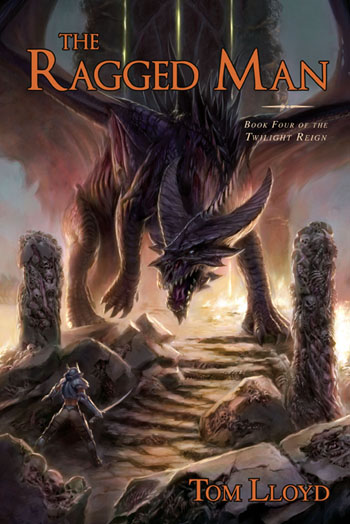

Cover art copyright © 2010 by Todd Lockwood